In the (Female) Mind’s Eye: Regarding Pain

Regarding the Pain of Others

By Susan Sontag

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 131 pages, $20.

* * *|

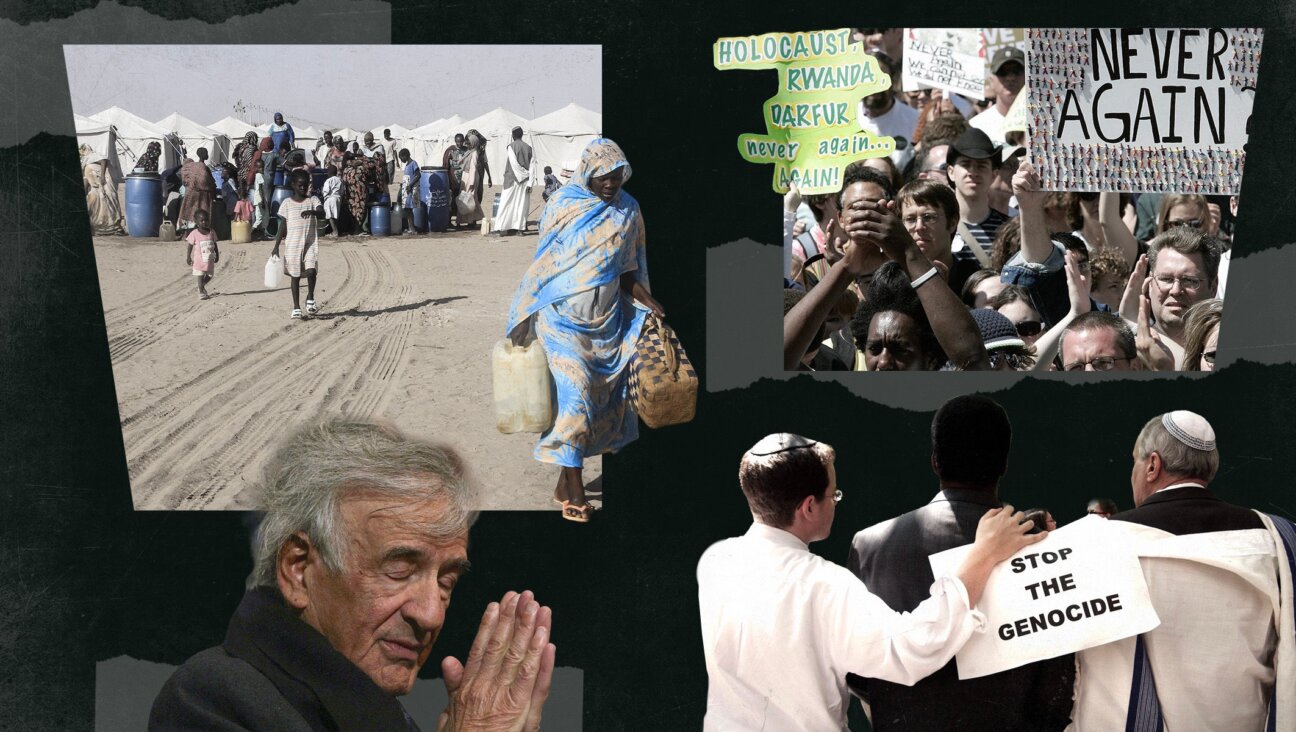

Lately, we have come to expect war photography as unassailably accurate and objective as the news with which it is featured, as unslanted as its accompanying text. A photographer of the recent war in Iraq was fired after he combined two busy pictures to create one clear one, charged with manipulating the news. Yet, as Susan Sontag recounts in “Regarding the Pain of Others,” a history of how the camera has reported war and associated horrors from the 19th century to the last decade of the 20th, famous photographers throughout history contrived their pictures — including the raising of the flag on Iwo Jima as well as Matthew Brady’s Civil and Crimean War shots.

Significantly, the book includes not one picture, as though the photographs Sontag so meticulously describes might distort, color or unbalance her rational, intellectual response to them. Indeed, although she has produced novels, plays and movies, Sontag is preeminently a critic of our culture, an essayist whose most influential work has been to interpret social phenomena. Without disseminating any narrowly focused, doctrinaire ideology, she belongs with other pioneering literary women in English and American literature such as Jane Austen, George Eliot, Virginia Woolf, Mary McCarthy, Cynthia Ozick and Grace Paley. All of these, and others like them, have opened vistas hitherto obscured in various ways. A bold, confident, cooly attentive vision, a broad tolerance, a capacity for direct unvarnished statement characterize all. For all their skill in observation and writing, even their greater male contemporaries generally fail to give us the same worlds.

As though to emphasize her consciousness of her own place in this pantheon, Sontag begins her latest essay by referring to Woolf’s distinction between the ways men and women regard war. “Men make war,” she writes. “Men (most men) like war, since for men there is ‘some glory, some necessity, some satisfaction in fighting’ that women (most women) do not feel or enjoy.” Sontag says that Woolf lets “subside” her intimation that men and women — “we” — can ever regard war similarly. “No ‘we,’” writes Sontag, “should be taken for granted when the subject is looking at other people’s pain.”

It is this special, unapologetic, entirely open view on which Sontag elaborates. It offers all readers a landscape too often neglected or blurred, in whole or in part. Very explicitly, Sontag brings to her examination of suffering the sympathy and empathy of a woman, a wife, a mother, a creative nurturer. Inevitably, one recalls the distinction, made without caricature by Jerry Seinfeld, between a man’s and a woman’s use of a remote control: Men, who restlessly surf the television screen, hunt; women, who stick to one program, nest. Nothing necessarily wrong with either, of course, but each finds somewhat different satisfactions that the other may slight. The nurturing woman essentially identifies with every victim but also senses, apprehends, acknowledges the ultimately incomprehensible impulses of those inflicting pain, thus assimilating in her vision the total universe in which pain occurs.

Only in the last portion of her thoughtful, careful and patient survey of photography’s presentation and implicit “interpretation” of horrors does Sontag fully engage with how photographs enable us to feel more deeply, understand more sensitively, think more knowledgeably and relate more personally to the awful experiences of others. However powerful a response a photograph may evoke by capturing a fleeting scene, it cannot provide, as words can, the full context of the history and rumination in which the shot is embedded, which only an analytical and sensitive observer — like Sontag — can add.

Morris Freedman’s essays and reviews have appeared in Commentary, the American Scholar and other publications. He teaches at the University of Maryland.