Understanding the Myth and Music of Bob Dylan

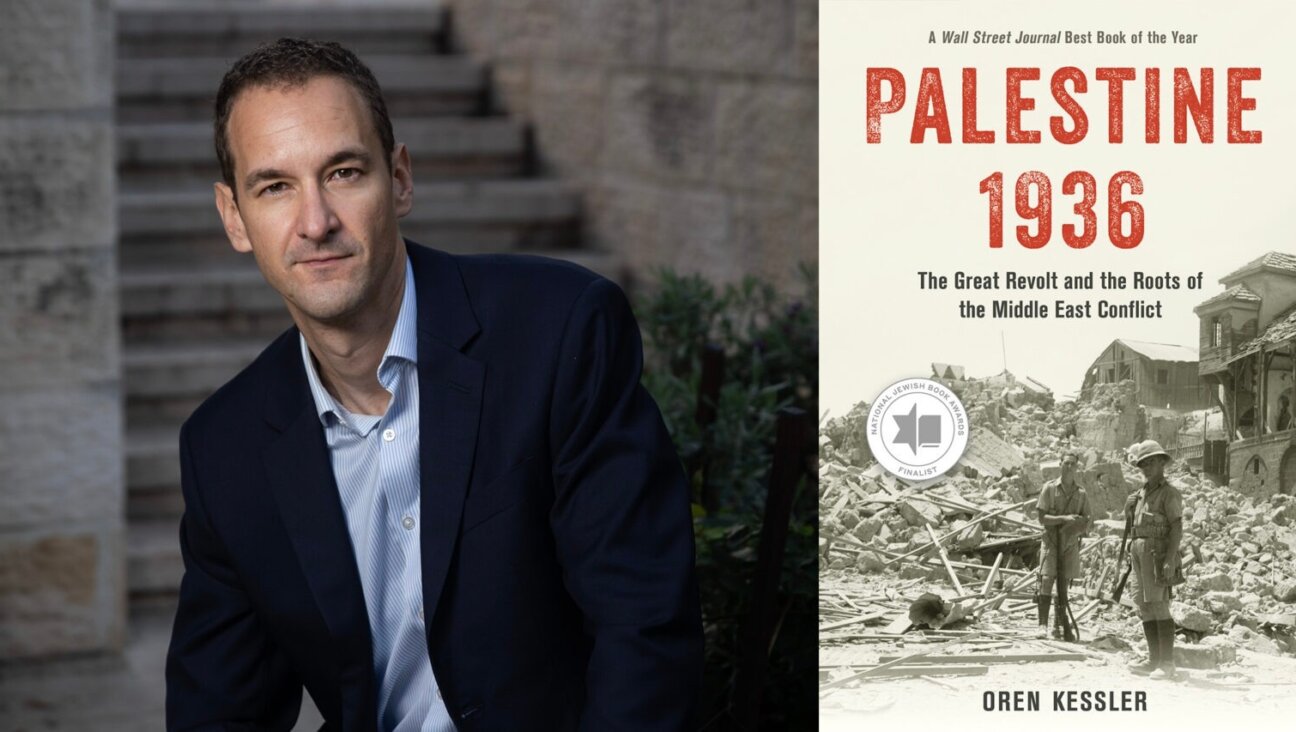

Midrashic: Greil Marcus teases out interpretations of Dylan. Image by THIERRY ARDITTI

Bob Dylan in America

By Sean Wilentz

Doubleday, 400 pages, $28.95

Bob Dylan by Greil Marcus: Writings 1968–2010

By Greil Marcus

PublicAffairs, 512 Pages, $29.95

Robert Zimmerman: Bob Dylan at a press conference on the Isle of Wight, 1969. Image by GETTY IMAGES

Choose almost any critical approach — biographical, political, religious, literary, musical, philosophical or historical — and chances are it already has been used to try to explain Bob Dylan and his work. Hundreds of books, thousands of articles and an ever-expanding universe of listservs, websites, magazines, academic courses and conferences sing Dylan’s loyal chorus of commentary. A few months away from turning 70 (May 2011), and primed to enter his sixth decade on the public stage, Dylan continues to wave his baton in every direction, urging the chorus onward — even though we know he’s not much for choruses.

Consider Dylan’s activity in the months of September and October alone: The fall leg of his Never Ending Tour crisscrossed North America again. No major artist of his standing plays as much. Columbia Records rereleased his first eight albums, as well as “The Witmark Demos: 1962–1964,” the ninth installment of his officially sanctioned outtakes, live performances and oddities, in “The Bootleg Series.” An exhibition of Dylan’s original paintings, titled “The Brazil Series,” opened in Denmark’s largest art museum.

New contributions by two writers in the first row of the Dylan chorus of commentary have arrived this fall, as well: “Bob Dylan in America” by Sean Wilentz, and “Bob Dylan by Greil Marcus: Writings 1968–2010.” The almost simultaneous release of works by Wilentz, an esteemed Princeton University scholar of American history and “historian-in-residence” at www.bobdylan.com, and Marcus, the most creative and lucid of all thinkers about Dylan, provides an opportunity to take stock again of the question people have been asking about Dylan since he arrived in New York City in 1961 “already a legend,” in the words of former partner Joan Baez. So, what is the best way to understand him?

Because Dylan has been one of the most influential artists of the past century, refining the critical approach to his work has repercussions not only for those of us still fascinated by his continuing contribution to popular culture, but also for anyone who cares about how popular culture is seized by the world.

Midrashic: Greil Marcus teases out interpretations of Dylan. Image by THIERRY ARDITTI

In “Odysseus’ Scar,” the first chapter of his study “Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature” (1953), Erich Auerbach presents the history of Western literature as a choice between two creative paths. “It would be difficult” he writes, “to imagine styles more contrasted than those of these two equally ancient and equally epic texts.” The first epic mode is that of Homer, a realm where the narrator shines an overwhelmingly bright light on the characters and situations of his story. There are no gaps in the Homeric narrative. No details of circumstance or motivations of characters are left unexplained.

The second mode is biblical. Here, Auerbach finds a storytelling tradition dependent on gaps and fragments “fraught with background.” For biblical literature and its narrative descendants, motivation and detail are purposely obscured so that a life of interpretation and commentary thrives continually. While biblical scribes and their rabbinic heirs cluster around laconic narratives that leave the burden of imagination to interpreters, the Homeric mode prefers richly detailed depictions of reality in which the responsibility for imagination lies primarily with the storyteller.

In context of Auerbach’s grand theory, it is useful to think of Wilentz, a historian, as a Homeric Dylan commentator, while Marcus, a cultural critic, takes the midrashic role. Both authors mine the gaps of Dylan’s world, shedding light on his work to understand where this material comes from, how it works and what it means. Yet for the most part, the light each writer shines reveals different things. Wilentz uses history to smooth and explain the invitingly deep contours of Dylan’s work. Marcus seeks out those places where Dylan’s work demands commentary, weaving imaginative, unexpected interpretations. He often widens those gaps further, allowing the echoes within them to resonate in new ways.

Wilentz describes in the book’s introduction his motivation for writing “Bob Dylan in America”:

I have been curious about when, how, and why Dylan picked up on certain forerunners, as well as certain of his own contemporaries; about the milieu in which those influences lived and labored and how they evolved; and about how Dylan, ever evolving himself, finally combined and transformed their work. What do those tangled influences tell us about America? What do they tell us about Bob Dylan? What does America tell us about Bob Dylan and what does Dylan’s work tell us about America?

Beginning with the Popular Front social movement of the 1930s and ’40s — well-traveled ground for thinking about Dylan’s roots, but distinctive in proposing Aaron Copland as a key figure — Wilentz traces Dylan’s antecedents and mentors through the Beats, particularly Allen Ginsberg. The book continues somewhat haphazardly, landing in “selected and arbitrary but far from random moments.” From chapters on concerts at the New York Philharmonic in 1964 and in New Haven, Conn., in 1975 (apparently, an important criterion for Wilentz’s choices of historical focus are events he attended), to a stellar chapter on the making of 1965’s “Blonde on Blonde,” through the foggy folk narratives of Dylan’s turnaround albums in the 1990s, up to his most recent work, Wilentz assembles a tableau of facts and influences upon which Dylan’s story and oeuvre fit neatly. Yet, providing copious detail of Dylan’s life and times forces into the background many of the powerful shadows of allusion, unpredictability and ambivalence that give power to Dylan’s work.

Though Marcus has earned a place as one of America’s most prominent cultural critics by extending his rock interests into literature, politics, history, religion and art, “Bob Dylan by Greil Marcus: Writings 1968–2010” traces the path of his career through perhaps his favorite topic — Bob Dylan. Particularly in the sections “New Land Sighted, 1993–1997” and “New Land Found, 1997–1999,” Marcus grounds Dylan in an understanding of American myth out of which all else, including American history itself, is a result. These sections represent the period during which Marcus wrote “Invisible Republic: Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes” (now titled “The Old, Weird America: The World of Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes”), mining the relationship between Dylan’s musical mythology of America and the mystic amalgam of traditional folk, blues and country from the first half of the 20th century, represented by the recordings on Harry Smith’s “Anthology of American Folk Music.” In his 1998 review of “Invisible Republic” in the magazine Dissent, Wilentz wrote that “the critic and the artist have locked into some strange, empathetic communication. Either Marcus has been reading Dylan’s mind or Dylan has read Marcus’s book — or, maybe, both things have happened. Whatever the case, ‘Invisible Republic’ ranks as the most brilliant study of Dylan’s work to date….”

Christopher Ricks’s “Dylan’s Visions of Sin” (Ecco, 2004) and Dylan’s own memoirs, “Chronicles: Volume One” (Simon & Schuster, 2004), now share the title of “Brilliant Studies of Dylan’s Work” because they model how Dylan — a combination of market-savvy rocker, Homeric bard and biblical seer — has carved out a place in popular culture for art “fraught with background.” As captured in a rich anthology ranging from reflections of a few lines to full essays, Marcus’s journey with Dylan has shown how music and myth live in the vision of an artist whose traditional, even ancient approach to art merges best with a midrashic rather than a historical critique.

So how best to understand Bob Dylan? Miles Davis, another modern master of American music, once said, “Don’t play what’s there, play what’s not there.” Playing what’s there and what’s not there as a critic — a mode familiar to Dylan playing out his influences as an artist, as well — Marcus allows Dylan’s work to be heard thicker, stranger, more boldly and with more imagination than we could hear it on our own.

Stephen Hazan Arnoff is the executive director of Manhattan’s 14th Street Y, which December 5 hosts “Bob Dylan and the Band: What Kind of Love Is This?” a symposium, gallery exhibition and all-star concert celebrating the music of Bob Dylan and the Band.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30