Palestinian-Led Movement To Boycott Israel Is Gaining Support

Uzbekistan-born diamond mogul Lev Leviev announced late in August that his company, Africa-Israel, was drowning in debt of more than $5.5 billion that it could not repay. Over the next two days, shares in the company’s stock plummeted by more than one-third. It was relentless bad news for one of the world’s richest men. His holding and investment company had lost $1.4 billion since 2008, mostly due to failed real estate investments in the United States.

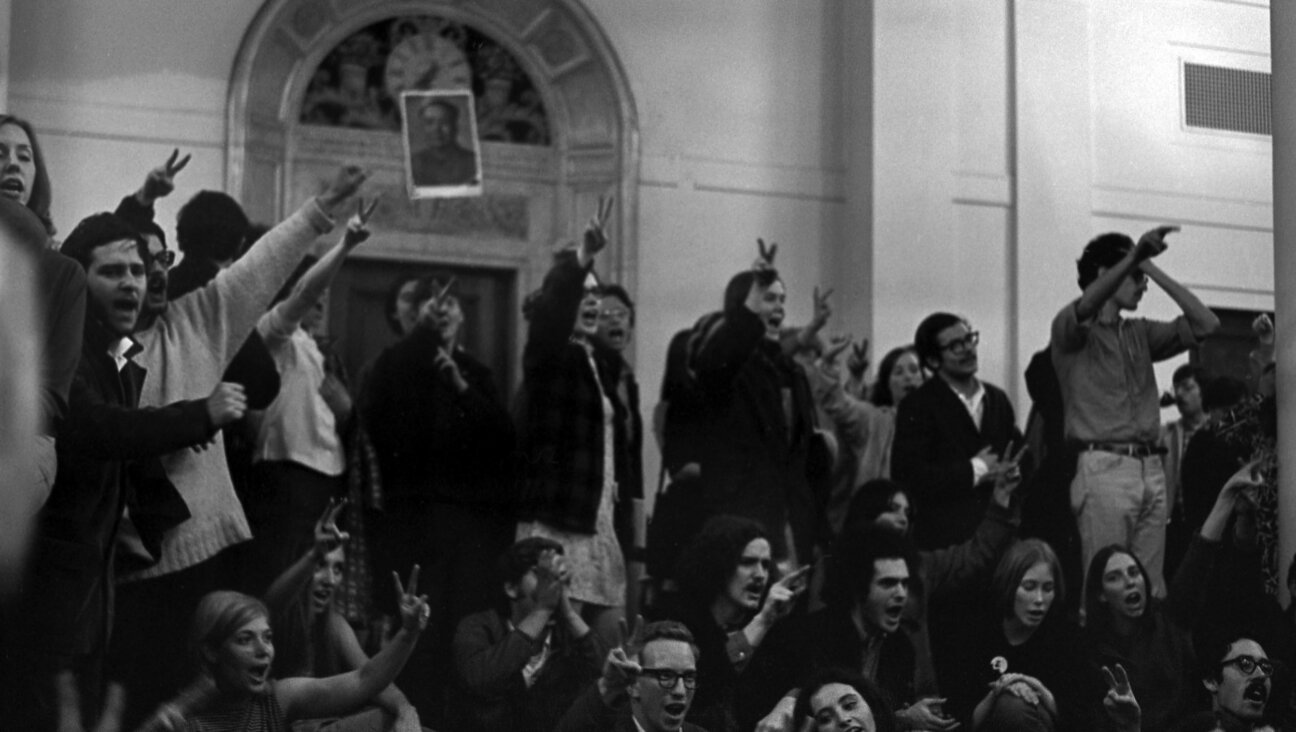

Watching Leviev’s precipitous downfall from the sidelines were pro-Palestinian activists. And they were cheering.

Though certainly not the cause of his financial collapse, for the past two years, these activists have singled out Leviev as one of their high-profile villains for his large contributions to West Bank settlements. And they have been effective gadflies. Several of the company’s major shareholders have divested their holdings from Africa-Israel after receiving complaints from clients. And at least two charities have declared publicly they will not accept Leviev’s contributions.

The pro-Palestinian activists are affiliated with the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement, an international coalition with the goal of isolating and discomfiting Israel just as South Africa’s apartheid regime was targeted in the 1980s.

Initiated by Palestinian groups in 2005 but strengthened by a network that takes in dozens of leftist organizations in Europe and the United States, the Global BDS Movement claims a number of recent successes. Especially in the wake of the Gaza incursion of last winter, groups associated with the boycott have now felt spurred to expand their efforts into even the sensitive realm of academic and cultural boycotts of Israel.

As Omar Barghouti, one of the Palestinian leaders of the BDS movement, told the Forward, “Our South Africa moment has finally arrived.”

Some major Jewish groups acknowledge BDS as a possible threat. “There are clearly a number of episodes building up here that would allow advocates of a boycott to say that slowly, slowly we are achieving what we want, which is the South Africanization of Israel,” said American Jewish Committee spokesman Ben Cohen. “I’m not sure that the increase in activity is quite as dramatic as some people would believe, but it’s clear to me that this discourse of boycott is being increasingly legitimized, and it would appear that some companies are responsive to it.”

The BDS movement is highly decentralized, with each group in the coalition allowed to choose its own targets as it sees fit. It has no articulated political vision. such as a one- or two-state solution to the conflict. The principles that guide the movement — as set out in a call for boycott, divestment and sanctions issued in June 2005 by a wide group of Palestinian civil society organizations — demand instead that Israel adhere to international and human rights law. The amorphous structure and broad goals appear to be responsible for many of the group’s appeal. But some who watch this movement closely contend that, in the end, even a “targetted” boycott is ultimately aimed at all of Israel.

The actual monetary impact of the movement is often unclear. But for activists seeking as much to affect Israel’s image in the public’s mind, money is not always the bottom line.

The campaign against Leviev is a good example. It was initiated by Adalah-NY, one of the handful of American groups in the BDS movement’s network. It was Adalah’s activists who chose to focus on Leviev’s construction projects in the West Bank and on contributions he has made to the Land Redemption Fund, which gives money for settlement development. Adalah-NY protesters first picketed the opening two years ago of Leviev’s diamond retail store, yelling at actress Susan Sarandon as she entered the Madison Avenue shop. Since then, the group has taken every opportunity to point out his connections to the West Bank settlements.

Lately, the fruits of this focus on Leviev have been piling up. On Sept. 11 TIAA-CREF, the giant pension fund, announced that it had divested from Africa-Israel last March after 59 of the company’s investors accused it of being “a company which violates human rights and international law.” UNICEF and OXFAM denied Leviev’s public claims to have given them generous contributions and added that they would not accept contributions from him because of his financial support for West Bank settlements. Also, in the past few weeks, a couple of Africa-Israel’s largest investors have sold their stock in Leviev’s company after receiving pressure from their clients. Most notable was BlackRock, the British subsidiary of the major Wall Street banking firm, which announced that it was divesting following concerns expressed by three client Scandinavian banks.

“Those aren’t small things,” said Andrew Kadi, a member of Adalah who is involved with the Leviev campaign. “People don’t completely grasp how serious it is when two of your top 10 or 12 shareholders divest. We’re talking about millions of dollars.”

Neither Leviev nor Africa-Israel responded to requests for comment.

Leviev’s trouble is just one of many recent signs of the movement’s higher profile. There was the protest joined by several celebrities in mid-September at the Toronto International Film Festival of the festival’s official cultural partnership with the city of Tel Aviv in celebration of the latter’s 100th anniversary. A few days earlier, Neve Gordon, a professor at Ben-Gurion University, wrote a controversial opinion piece in the Los Angeles Times, endorsing the BDS movement as the “only way to counter the apartheid trend in Israel.” This past June, the French company Veolia Environnement SA abandoned its multibillion-dollar project to build a light rail train system in Jerusalem after pressure mounted in France from BDS-affiliated groups. The activists counted it as one more victory.

Ironically, Barghouti, who appears to be one of the movement’s chief strategists, is currently in a master’s degree program in philosophy at Tel Aviv University — even though he is one of the founding members of the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel. He has been one of the activists strongly pushing the greater BDS movement in the direction of opposing any institution associated with Israel.

Asked about his affiliation with an institution he wants boycotted, Barghouti declined to discuss his personal life.

In an e-mail to the Forward, Barghouti emphasized that the BDS movement “does not adopt a particular political solution to the colonial conflict.” The main strategy, he wrote, “is based on the principle that human rights and international law must be upheld and respected no matter what the political solution may be. This was key to securing a near consensus in Palestinian civil society and a wide network of support around the world, including the Western mainstream.”

The exclusive focus on rights rather than on a political prescription for the conflict brings together both those who want to target Israel’s existence as a whole and those—mostly American activists—who stick to the more narrow issue of the occupation and settlement activity.

As far as Barghouti is concerned, BDS is a “comprehensive boycott of Israel, including all its products, academic and cultural institutions, etc.” But he understands “the tactical needs of our partners to carry out a selective boycott of settlement products, say, or military suppliers of the Israeli occupation army as the easiest way to rally support around as a black-and-white violation of international law and basic human rights.”

Cohen, the AJC spokesman, views this tactic as a transparent deception. “If you probe these groups a little deeper, you’ll find that really this is entirely ideologically motivated. They are just a bunch of radical groups that want to see the state of Israel eliminated,” he said. “That is the thread that unites all the disparate groups in the BDS movement, they all see BDS as a means to arrive at the goal of a world without Israel. I think that many people who might be troubled by Israel’s presence in the West Bank are going to run a mile when they see what the real agenda of these groups are.”

The activist group Code Pink: Women for Peace recently turned its attention to this type of targeted boycott, focusing on the cosmetics company Ahava. Based in the kibbutz Mitzpe Shalem, a settlement in the West Bank, Ahava was a convenient target for the group. After picketing stores that sold Ahava products — mostly mud masks and mineral salts from the Dead Sea — the Code Pink activists looked on with satisfaction as the company’s spokeswoman, “Sex and the City” star Kristin Davis, was dropped as an ambassador for OXFAM. The group gave its reasons in a statement, saying that it “remains opposed to settlement trade, in which Ahava is engaged.”

Nancy Kricorian, Code Pink’s New York City coordinator and the organizer of its Ahava campaign, dubbed Stolen Beauty, said that this push against the cosmetics company was effective precisely because it was tightly focused on a settlement operation. And yet, it also fell squarely within the guidelines of the BDS movement’s principles and objectives and was even cited by Barghouti as a successful model because it sullied Ahava’s name publicly.

Barghouti, Kricorian and other BDS activists attended the national conference of the U.S. Campaign to the End the Israeli Occupation, which took place on September 12 and 13 in Chicago. The organization is itself an amalgamation of dozens of smaller pro-Palestinian groups from across the country. Up until this conference, its BDS activity had also been narrowly focused on American companies involved in the West Bank. Specifically, they have targeted Caterpillar Inc. for manufacturing the bulldozers involved in settlement construction, and Motorola USA for the surveillance and communications equipment used by the Israeli army.

But according to David Hosey, national media coordinator for the campaign, the group resolved at the conference to extend its activities for the first time to the more sensitive cultural and academic boycott. Like many other pro-Palestinian activists, Hosey dated this willingness to increase boycott activity to the Gaza incursion of this past winter.

“It was a big shock to the system, and it caused a big sea change in what people were willing to do,” said Rebecca Vilkomerson, the national director of Jewish Voice for Peace, which, though supportive of the BDS movement, has not officially joined it.

Contact Gal Beckerman at [email protected]

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30